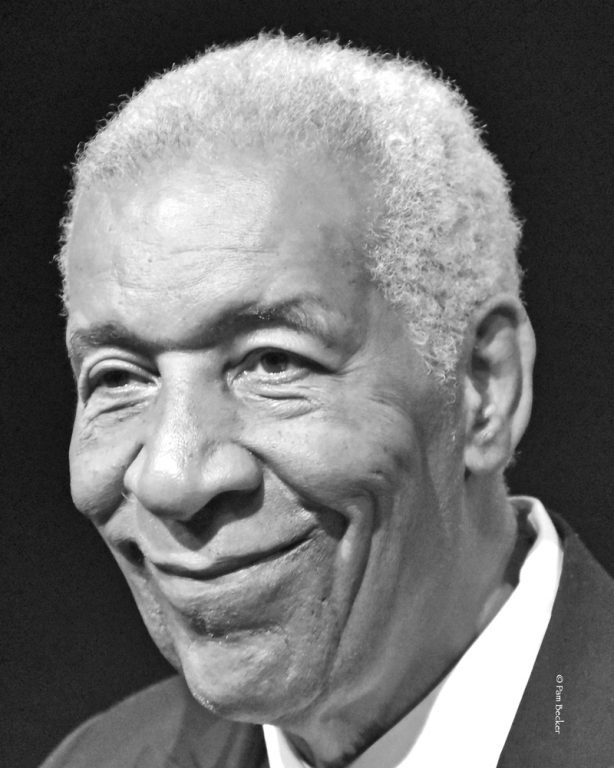

For more than three decades, Norman Malone distinguished himself as an educator in the Chicago Public Schools, conducting award-winning choruses and serving as a much-loved mentor to two generations of high school students. Little did people know: he is a gifted pianist and survivor of a savage assault.

This fall, the Grant Park Music Festival hosts its annual Advocate for the Arts Awards Benefit and honors an extraordinary presence in Chicago’s musical firmament.

For more than three decades, Norman Malone distinguished himself as an educator in the Chicago Public Schools, conducting award-winning high school choruses and serving as a much-loved mentor to two generations of high school students until he retired in 2001. Then, in 2015, an unlikely set of events sent his life in a new direction—word got out about his piano playing. This led to a CBS News profile, an award-winning documentary film, and the airing of a terrible family secret.

Norman Malone is a virtuoso. He also has disabilities. With little use of his right hand and foot, he nurtured his gift as a pianist—not in the schools where he taught but in the privacy of his home. With his own kids grown and his wife gone (she passed in 2003), there was no one to notice that he had doubled down on the piano—that is, no one but the neighbors. Judith Stein, the co-founder of the Hyde Park Jazz Festival, told The Chicago Tribune she would pause to listen to the music coming from her neighbor’s apartment on the way to the elevator.

“I was kind of blown away by it,” she said. “So I just stood outside of the door and listened.”

Norman Malone practices the piano in his Hyde Park living room

Standing 6’2”, Malone cuts a striking figure. With a calm, steady gaze, he is quiet, thoughtful, and serious. He walks with a pronounced limp and shields his right hand, which is stiffened from years of disuse. But his left hand—that’s where the magic happens.

Judith Stein finally met Malone in the hallway and told him she’d been listening; he invited her inside. This led to informal gatherings with neighbors and former colleagues from Lincoln Park High School. Eventually, his story came to the attention of the Tribune’s Howard Reich, who published an expansive, three-part profile in 2015, revealing the shocking circumstances of Malone’s disability.

Norman Malone was born in 1938 and lived with his family at the Ida B. Wells Homes in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood. He gravitated toward the piano at a young age and persuaded his parents to buy an instrument. Even as his musicianship developed, a sense of foreboding was settling over the family: Malone’s father, Quintis, was mentally ill and had become violent.

Children gather outside the Ida B Wells Housing Project in 1942

“According to my mother, what I could get out of her, was that he had advanced stages of syphilis, and he knew that he was going to die,” Malone told The Chicago Tribune. “And so, rather than burden my mother of raising three boys, he decided he was going to take us with him.”

On the night of May 24, 1948, Quintis Malone grabbed a hammer and attacked his sons in their beds. He then threw himself in front of a commuter train, committing suicide. All three boys survived the attack and underwent multiple surgeries and years of rehabilitation. All were paralyzed. Of the three, 10-year-old Norman was the only one to recover sufficiently enough to eventually live independently.

Even without the use of his right hand and foot, Malone continued to turn to the outlet that had nourished his spirit from the age of five—the piano. After a series of rejections from different instructors, he found a teacher who would work with him and steer him toward repertoire written for the left hand alone. After high school, he auditioned and won a spot in the music program at DePaul University. It was around that time that he began a lifelong quest to master the Piano Concerto for the Left Hand by Maurice Ravel.

DePaul University’s Frank J. Lewis Center on Wabash pictured ca. 1960 was the one-time home of the DePaul University School of Music. Today it houses the DePaul College of Law.

By the time he graduated from DePaul, Norman Malone had left his past behind (or so he thought). He married, started a family, and became a Chicago Public School teacher. People no longer asked him about his disabilities—and he didn’t volunteer the information, even shielding his past from his own children.

Malone went from teaching at Whitney Young High School on the city’s west side to Sullivan High School in Rogers Park and then was asked to establish a choral program at Lincoln Park High School. He accepted the challenge and, in no time, had assembled one of the finest youth choruses in the state. Traveling to competitions, the choruses of Lincoln Park High School consistently earned superior ratings. An inspiration on stage and off, Malone taught a number of students who became professional musicians.

“Mr. Malone taught me the best vocal warmups, breathing techniques, and posture, all of which I use to this day,” said jazz singer Kimberly Goron. “Oh yes, also, brilliant little tricks that help me work through any problem spots when learning new compositions. I am so grateful for these gifts he has given me.”

Referring to his students as his “little children,” he became a role model to them. Gordon, who attended Lincoln Park High from 1982-86, said to The Chicago Tribune “he made me want to go to school.”

“Students are under a lot of pressure,” said Malone, referring to the academic standards at Lincoln Park High, which is an International Baccalaureate school. “Music is a way of relieving that tension,” he said. Through the years, he served as a shepherd to youths who struggled with everything from bullying to troubles at home. Students and colleagues remember Malone as being friendly, firm, and always willing to stand up for what was right. At the same time, no one seemed to realize that he himself had survived an appalling act of injustice.

By the 2010s, retirement for Norman Malone had become a time for music and solitude. He practiced the piano for hours each day and became a regular at a favorite jazz club on the city’s South Side. It was during one of those outings that he met The Chicago Tribune’s Howard Reich. With the neighbor serving as a self-appointed press agent, Reich managed to glean the major points of Malone’s story and decided it was one he needed to tell. After exhaustive research and hours of interviews, Reich issued a three-part profile on Norman Malone in the Tribune over the 2015 Thanksgiving weekend.

Nearly seventy years after the attack, this odyssey of survival, artistry, courage, and grace became a source of wonder and inspiration for countless others. Malone started receiving offers to perform. The television journalist Steve Hartman featured his story on CBS News, and Howard Reich went to work transforming the tale into a documentary for Kartemquin Films.

Norman Malone performs Maurice Ravel’s Piano Concerto for the Left Hand

Since its release in 2021, the film For the Left Hand has captivated viewers on PBS and at film festivals across the country. Most thrilling of all, it chronicles the fulfillment of a lifelong dream for the man at the center of it all. After 60 years of practicing Ravel’s Piano Concerto for the Left Hand, Norman Malone took a seat at a piano in West Hartford, Connecticut, and performed the piece with the West Hartford Symphony Orchestra and conductor Richard Chiarappa. Malone was 79 years old.

On Thursday, October 27, Norman Malone will receive an Advocate for the Arts award from the Grant Park Orchestral Association, with Howard Reich serving as the presenter. The evening also honors the philanthropic work of the law firm Epstein Becker Green and will include a reception and dinner.

Piano Repertoire for the Left Hand

Pianist Paul Wittgenstein had only been serving in the Austro-Hungarian army for a few weeks when he took a bullet to the right elbow. It happened at the Battle of Galicia, one of the early conflicts of World War I. The young Austrian awoke to a new reality: he had lost his right arm and was a prisoner of war.

Just weeks before, Wittgenstein had been working toward a promising career as a concert pianist. Finding himself at a prison camp in Omsk, Siberia, he took a piece of charcoal and drew a piano keyboard across a wooden crate and began a rigorous practice routine. After his return to Vienna, Paul Wittgenstein made it his mission to commission left-handed piano pieces from the greatest composers of his time, including Richard Strauss, Sergei Prokofiev, Erich Korngold, and Maurice Ravel.

Normal Malone, whose story has been shared nationally, will be the featured performer at the West Hartford Symphony Orchestra’s Autumn Classical Concert Oct. 27.

By Rob Kyff, submitted by West Hartford Symphony Orchestra

The one-handed pianist Norman Malone, who astounded audiences when he performed with the West Hartford Symphony three years ago, will make a triumphant return to the Roberts Theater for the Symphony’s Autumn Classical Concert at 3 p.m., Sunday, Oct. 27.

Malone, 82, whose uplifting story has been told on the CBS Evening News (see video clip below) and by several national newspapers, will perform “Diversions,” Benjamin Britten’s piano concerto for the left hand.

In 1948, Malone was a 10-year-old boy in Chicago who dreamed of being a concert pianist. He’d been taking piano lessons since the age of 5 at Holy Angels Catholic Church and practiced every day on a used upright piano in his parents’ apartment.

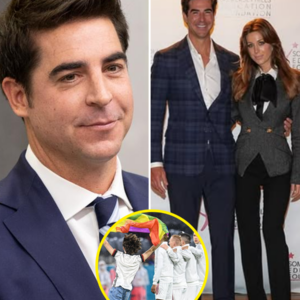

Norman Malone. Photo credit: Pam Becker (Courtesy of WHSO)

But his musical dreams were shattered on May 25, 1948, when he and his brothers suffered an unimaginably horrible assault by their mentally-deranged father.

Malone sustained a severe brain injury in the attack, rendering his right hand permanently useless. But, despite intense pain, physical disabilities and psychological trauma, Malone never lost his love for music.

Not long after leaving the hospital, he resumed his piano lessons, playing and mastering compositions specifically written for the left-hand only. After graduating from DePaul University’s School of Music, he taught choral music in Chicago public schools for 30 years, retiring in 2001.

Three years ago, in 2016, he played with an orchestra for the first time ever when he performed Maurice Ravel’s “Piano Concerto for the Left Hand” with the West Hartford Symphony Orchestra.

The Oct. 27 concert, the first of the Symphony’s 18th season, will also feature three pieces, specifically chosen to complement and balance the Britten composition Malone will be performing: Ludwig van Beethoven’s overture to his opera “Fidelio,” Georges Bizet’s “L’Arlesienne Suite No. 2,” and Jean Sibelius’ “Finlandia.”

“The Britten piece is a series of 11 variations, with brief pauses between movements,” said West Hartford Symphony Orchestra Director Richard Chiarappa, “while Beethoven’s overture to ‘Fidelio’ and Sibelius’ “Finlandia” are single-movement pieces, self-contained from beginning to end. Bizet’s ‘L’Arlesienne’ has four separate movements and is the closest in structure to the Britten.”

Chiarappa said he first learned of Malone’s poignant story three years ago when he read a profile of him by Chicago Tribune music critic Howard Reich. “I was moved to contact Norman because of our similar childhood backgrounds in playing piano, realizing how lucky I was to be able to continue studying and practicing, while his hopes had been cut short,” Chiarappa said.

When Chiarappa telephoned Malone to invite him to play with the symphony, he discovered that, by amazing coincidence, Malone’s son, daughter-in-law and granddaughters lived in West Hartford. The stars had lined up, and Malone agreed to perform.

“When he was with us in 2016,” Chiarappa said, “the orchestra fell in love with this gentle man right away. They realized that playing with an orchestra was new to him, that we were the first one to do so, and that he had never even rehearsed with an orchestra before. That motivated them to do all they could to help him and support him musically.”

Malone’s 2016 performance with the Symphony was received so warmly that Chiarappa decided to invite him to return this year. This year’s concert will be filmed by the Chicago documentary company Kartemquin Films, which has been working on a film about Malone that’s set to premiere in Chicago this spring. Kartemquin, which has won six Emmys, three Peabody Awards and four Academy Award nominations, hopes that the film about Malone will be screened at the Sundance Film Festival this winter.

Also in the audience on Oct. 27 will be Howard Reich, the journalist who first brought Malone’s story to national attention.